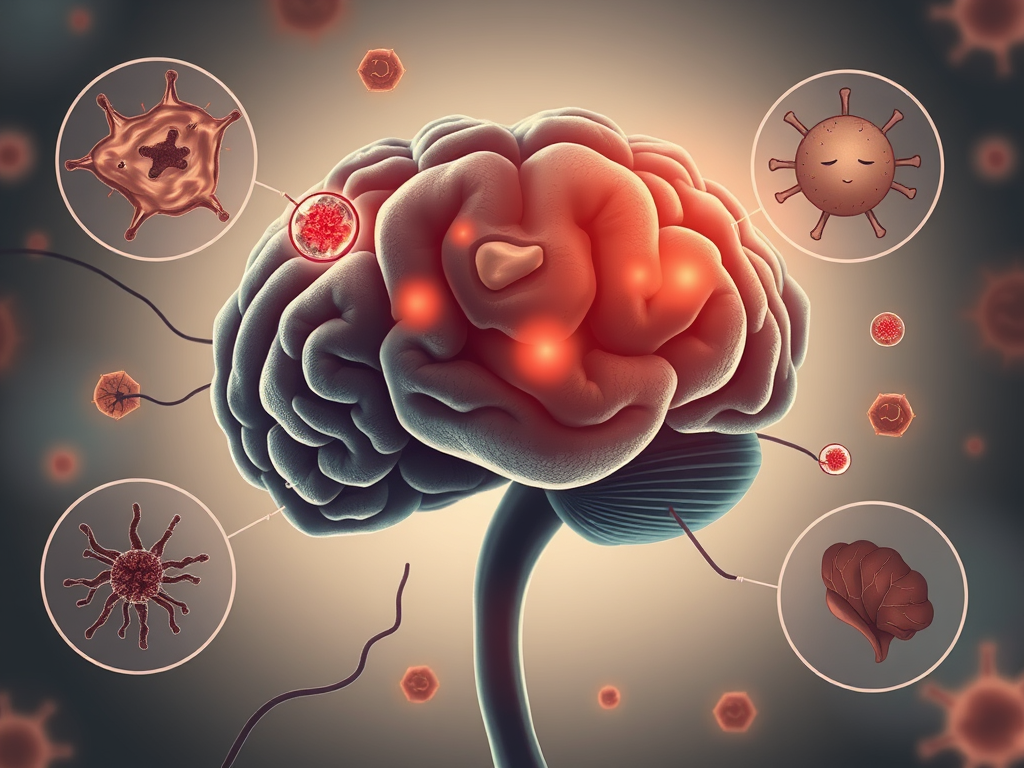

What is inflammation? You probably never thought inflammation will have anything to do with mental illnesses. Surprisingly, recent search has revealed a causal relationship between inflammation and depression.

Inflammation refers to the body’s immune response, which is generally activated by irritation, injury, or infection. Common symptoms of inflammation include redness, swelling, and pain. The inflammatory response is mediated by a variety of cell types. The immune system is composed of the innate and adaptive immune systems. The innate immune system includes macrophages and dendritic cells, which, when activated, produce cytokines that recruit immune cells to the infected location. Cytokines are proteins that can enhance or reduce the inflammatory response. These include pro-inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF-ɑ), some interleukin forms (e.g. IL-1β, IL-6), prostaglandins, or interferons. These cytokines and inflammatory factors not only amplify the immune response, but they also indicate the presence of inflammation. To transition to the adaptive immune response, dendritic cells present antigens– foreign molecules such as viruses–to activate lymphocytes. Lymphocytes are white blood cells that are a key component of the adaptive immune system and include B and T cells. Activated B cells become plasma cells, which produce antibodies that can neutralize antigens. Activated T cells become 1) cytotoxic T cells, which induce apoptosis 2) T helper cells, which influence activity of other immune cells 3) regulatory T cells, which regulate immune response to prevent autoimmunity. Some B and T cells become memory cells, which can facilitate a quicker response to the same pathogen in future. There also exist immune cells that are specific to the immune response of the brain, including microglia and astrocytes, which behave like innate immune cells. They can also be referred to collectively as glial cells, which are non-neuronal cells in the brain.

Emerging research shows that inflammation may have a significant role in depression. A meta-analysis of individuals with depression found that 75% of participants had low-grade inflammation (CRP levels greater than 3 mg/L, the threshold for what is normal). Similarly, positron emission tomography (PET) scans of translocator protein 18 kDa (TSPO) – an inflammatory marker – have consistently shown greater TSPO binding in both the prefrontal cortex (PFC) and anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) areas of the brain in participants in the midst of a major depressive episode. Both the elevation of proinflammatory factors and the decrease of anti-inflammatory factors are seen in both peripheral and cerebrospinal fluid and correlate with depressed patients’ symptoms and disease duration. Additionally, the remission of depressive symptoms is accompanied by a decrease in inflammatory factors. Accordingly, a variety of antidepressants result in the downregulation of a multitude of peripheral inflammatory markers and inhibit neuroinflammation. Overall, studies suggest that elevation of inflammation is correlated with more severe depression, higher recurrence of depressive symptoms, more adverse effects on brain function, such as impaired brain connectivity within motivation and reward circuits, and increased suicidality. Though much research into the relationship between inflammation and depression is centered around inflammation within the brain, it is still viable to measure peripheral inflammation in this context since it correlates with central nervous system inflammation. Peripheral inflammatory markers can get into the brain by either crossing the blood-brain barrier through leakage zones of less strictness or by activating various cell types, such cerebrovascular endothelial cells, which would be able to allow cytokines and other inflammatory factors into the brain.

There are numerous studies supporting the correlation between depression and inflammation, while other studies exist that find no association between elevated levels of CRP and IL-6 (common inflammatory markers). Thus, the relationship between depression and inflammation is still unclear.

Research suggests that inflammation may play a causal role in depression. One longitudinal study found a positive correlation between participants with elevated IL-6 and CRP levels at age nine and their likelihood of depression at age eighteen. Additionally, a review found that cancer patients with hyperactivity of the HPA axis caused by cancer and anticancer treatments, which led to subsequent inflammation, exhibited increased depressive-like symptoms.

One potential mediator between inflammation and depression is glutamate, a common excitatory neurotransmitter. Activated microglial cells may cause excessive release of glutamate, which leads to hyperactive signaling of glutamate receptors, which ultimately results in synaptic dysfunction and destruction. Additionally, glutamate diffusion away from the synapse contributes to loss of neurotransmission specificity, which can worsen depressive-like behaviors. Glutamine is also involved in the glutamate-glutamine cycle. Glutamine, the precursor to glutamate, may also play a role. One study found a correlation between depression severity, elevated levels of glutamine, and elevated glutamine-to-glutamate ratios in patients with depression. There have also been differences in cycle components that have been observed in postmortem brain tissue from healthy individuals and those with MDD.

Not only are molecular biomarkers of depression affected by neuroinflammation, but depression symptoms are as well. Two common symptoms of depression are anhedonia and amotivation, and they have been consistently shown to be affected by inflammation levels. Inflammation likely disrupts dopamine activity in reward circuits, contributing to anhedonia (loss of pleasure) and reduced motivation. Dopamine is a neurotransmitter associated with reward and motivation. Inflammation can dampen dopamine activity within reward circuits, resulting in disrupted frontostriatal functional connectivity (activity between brain regions) and ultimately mediating motivational and behavioral responses. In essence, inflammation can negatively influence the neural circuits underlying motivational symptoms closely related to anhedonia. This is further supported by research showing a significant correlation between cytokine levels (central IL-6 soluble receptor (IL-6sr) and peripheral CRP levels) and reduced motivation and anhedonia (amongst other depressive symptoms).

Additionally, inflammation affects signaling in brain regions directly related to depression. One study of depressed patients specifically found a correlation between plasma CRP levels and decreased connectivity between the ventral striatum and ventromedial PFC (vmPFC). The change in connectivity between these areas has been shown to be correlated with the severity of anhedonia. A clinical study involving the administration of IFN-α, an interferon, for 4–6 weeks in fourteen individuals without depression both induced anhedonia and reduced bilateral activation, or activation on both hemispheres of the brain, of the ventral striatum in an fMRI reward task. Lastly, reduced motivation has been correlated with levels of TNF-α within the central nervous system.

Source: Roger Li Curieux Academic Journal, issue 50